The majority of CISOs and GRC leaders agree that the definition of PHI is straightforward; health information combined with something that links it to a person brings it into scope.

The challenge is applying that definition to the way websites actually operate. Pages can introduce a health context through the tasks they support or the information they present. And identifiers can surface through cookies, IP addresses, and device signals.

HHS/OCR’s tracking-technology bulletin notes that these tracking tools can then collect these signals in ways that can disclose PHI to unauthorized parties.

These conditions are common across healthcare sites, and they influence how “PHI or not” should be evaluated. Inputs, implied context, and linkability often converge in ways that require a more careful assessment than the surface of the page suggests.

This guide covers twelve cases where clearer boundaries help. Each one shows how HIPAA’s definition applies in practice and how to implement simple controls to ensure compliance.

What You Will Learn

- Distinguish PHI from PII and apply HIPAA’s test for individually identifiable health information.

- Understand how OCR’s tracking-technology guidance maps to 12 common website edge cases.

- Implement concrete tag-manager recipes in GTM, Adobe Launch, and Tealium to block risky pixels and tags.

- Apply a simple four-step decision framework to classify PHI confidently and avoid common implementation mistakes.

Note: The information in this article is provided for general educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice, regulatory guidance, or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances.

What is PHI? HIPAA’s definition for website tracking

Under HIPAA, information is protected when it is both (1) about someone’s health, care, or payment and (2) individually identifiable. HHS frames this plainly: to be protected, it must meet the definition of protected health information, individually identifiable health information held by a covered entity or its business associate.

In other words, health data without identifiers isn’t PHI; identifiers without health data are Personally Identifiable Information (PII), not PHI.

HIPAA’s de-identification rule lists standard identifiers (name, complete address, email, etc.). When any of these or comparable clues can reasonably link a health context to a person, the data tips into PHI.

Why HIPAA website tracking creates hard calls:

HHS/OCR’s tracking-technology guidance notes that certain tools can collect information tied to health-related activity, such as scheduling, intake, or portal use. In 2024, a federal ruling narrowed one part of this guidance by holding that an IP address and a visit to a public, unauthenticated health-topic page do not, on their own, constitute individually identifiable health information. The ruling did not change expectations for authenticated areas or for situations where actual health information is disclosed.

These nuances make classification more complex. Indirect identifiers, inferred health activity, and contextual signals such as logged-in sessions can shift how data should be viewed.

With this baseline in mind, teams can approach the borderline cases more consistently and connect each determination to practical tag-manager controls.

PHI vs. PII: Key Distinctions for Website Tracking

| Element | PHI (HIPAA) | PII (General Privacy) |

| Definition | Individually identifiable health information held by covered entities or business associates | Any information that identifies an individual |

| Health context required? | Yes (must relate to health, care, or payment) | No |

| Examples | Email + appointment type, IP + symptom entry, hashed email + prescription refill | Email address, name, phone number |

| Regulated by | HIPAA Privacy Rule, OCR enforcement | State laws, FTC, sector-specific regulations |

| Website risk | Tracking pixels on authenticated portals, condition pages with user input, and scheduling flows | Newsletter signups, general contact forms |

| De-identification standard | Remove 18 specific identifiers (45 CFR 164.514) | Varies by jurisdiction |

12 HIPAA website tracking edge cases: When data becomes PHI

The twelve edge cases outline how HIPAA’s PHI definition and OCR’s tracking guidance map to common website patterns, and how to align each classification with supporting controls in your tag manager.

Edge Case 1: IP address on a public symptom checker

This scenario is likely PHI. When a user enters health information and an identifier (e.g., an IP address or other signals) is collected by or disclosed from a regulated entity’s site, it may constitute PHI. PHI requires health information with an identifier. Entered symptoms with identifier meet that bar. The fix is to block all tracking on symptom-checker pages and keep such tools behind HIPAA-eligible controls.

Edge Case 2: Appointment confirmation number only

This scenario is not PHI (as described). The confirmation page shows a unique appointment ID with no name, condition, or other health details. An identifier alone, without any associated health information, does not constitute PHI. You can track the page view, but ensure no diagnosis, treatment information, or patient identifiers appear in the URL, data layer, or events.

Edge Case 3: “Cardiology department” in a public URL

Whether this scenario is PHI or not depends. For unauthenticated public pages, a court vacated the bulletin’s broader view that “IP + visit to a public health-topic page” is automatically IIHI. If no user inputs or additional signals tie the visit to the person’s care, it may not be PHI. If the visit involves entering data (e.g., appointment information) or combining it with other identifiers relating to care, it can be PHI.

As a general practice, avoid including condition terms in URLs sent to third parties and use generic IDs instead. You can also block pixels on pages where users provide information.

Edge Case 4: Time spent on a diabetes article (public page)

This isn’t PHI by default. Pure content consumption on an unauthenticated public page, without user inputs or additional identifiers tied to care, may not be PHI. But if the tool captures identifiers and user-provided information related to care, it can become PHI.

To prevent this, simply disable session replay on condition pages or ensure it never captures user inputs/identifiers.

Edge Case 5: Chat widget on an authenticated patient portal

This scenario is likely PHI. Authenticated portals generally involve PHI. Page context, identifiers visible to the widget, or any health-related messages make the data PHI. Use HIPAA-eligible chat with a BAA, scope access tightly, or keep chat out of authenticated areas.

Edge Case 6: Newsletter signup on a cancer center site

This might qualify as PHI in some cases. An email address is an identifier, but unless the context ties the submission to the individual’s health, treatment, or payment, it may not be PHI.

It’s only if the flow associates the email with care-seeking (e.g., appointment, symptoms, treatment intent), it can become PHI. Keep marketing signups separate from care journeys; avoid mixing with portal sessions and limit what’s collected.

Edge Case 7: Telehealth “waiting room” pixel

This scenario is likely PHI. The telehealth waiting room pixel is part of receiving health care; identifiers plus encounter context typically constitute PHI.

To prevent this, consider blocking third-party pixels on waiting room/visit pages and don’t rely solely on HIPAA-eligible telemetry.

Edge Case 8: Hashed email with prescription-refill page

This is PHI. A hashed email remains an identifier in many contexts, and a prescription-refill page clearly relates to health care. Together, they meet the definition of individually identifiable health information.

In this case, it is helpful to keep identifiers, including hashed values, and medication-related context out of ad or analytics tools. Third-party pixels are best limited on webpages loading medication and refill flows.

Edge Case 9: ZIP code + age + appointment type

This scenario is likely PHI. The appointment category is health information; combining it with quasi-identifiers can make the individual reasonably identifiable.

It is generally helpful to avoid sharing these combinations with third parties. But if analysis is needed, aggregate well beyond HIPAA’s de-identification thresholds or keep it in HIPAA-eligible systems.

Edge Case 10: Google Analytics (GA) on authenticated bill-pay

This scenario is likely PHI: GA tracks “view bill” with amount (no name shown) in a logged-in experience. Payment for health care is PHI when linked to an individual encounter/account. Authenticated billing flows are within HIPAA scope.

Since GA is not HIPAA-eligible, consider blocking GA and third-party pixels in authenticated billing; use HIPAA-eligible analytics.

Edge Case 11: Session recording on insurance verification (fields “redacted”)

This scenario is likely PHI. Session replay runs on insurance verification forms with masking enabled. The activity itself (insurance verification for health services), along with any identifiers, generally falls within PHI. Replay tools typically store recordings with third parties. Do not use session replay on insurance or patient-info forms; confine analysis to HIPAA-eligible methods.

Edge Case 12: Retargeting pixel on COVID-testing schedules

This is PHI. A retargeting pixel fires when users visit the COVID-19 test scheduling. Scheduling a health service is health information; browser IDs/cookies are identifiers.

It is generally helpful to avoid using retargeting pixels on condition-specific scheduling pages and similar care-related flows.

Tag Manager Implementation

In our experience, the cleanest way to avoid website-side HIPAA issues is to make one rule hold everywhere, to have PHI pages never fire marketing tags. What we see work reliably is a vendor-agnostic pattern where PHI-risk routes, such as portal, telehealth, scheduling, and results, carry a simple page flag. Tag managers then use built-in conditions to prevent non-essential tags from loading.

Google Tag Manager Approach

The core pattern in GTM starts with creating a variable that flags PHI pages. You can use a custom JavaScript variable or a data layer variable. Set up a variable called “isPHIPage” that pulls from your data layer, and on PHI-designated pages, push the flag into the data layer with a simple statement like dataLayer.push({‘phiContext’: ‘true’}).

Once that variable exists, blocking becomes straightforward. Open each marketing tag (Google Ads, Facebook Pixel, retargeting scripts) and add an Exception trigger under the Triggering section. The exception should fire on page views where isPHIPage is true, preventing the tag from loading on those pages.

Alternatively, you can create trigger exceptions based on URL patterns if your PHI pages follow predictable paths like /portal/,/telehealth/, or /scheduling/. GTM’s trigger and blocking logic is documented and supports this kind of conditional suppression.

Adobe Launch Approach

Adobe Launch follows a similar pattern but uses Data Elements and Rule Conditions. Create a Data Element called “PHI Page Check” using the Custom Code type. The code should evaluate the URL path or check page metadata to determine PHI context. A simple implementation might check if the pathname includes known PHI routes or if a page-level variable indicates PHI content, returning ‘true’ or ‘false’ accordingly.

With that Data Element in place, configure your marketing rules to respect it. Open each rule and add a condition that requires “PHI Page Check does not equal true” before the rule executes.

This prevents the rule from running on PHI pages while allowing it everywhere else. Adobe’s documentation confirms that rule conditions and data elements can control when tags fire, making this a supported and reliable pattern.

Moreover, you can create rules with conditions that evaluate page context via URL or Data Elements. For PHI-designated pages, configure rules to prevent marketing and non-essential analytics from executing. Adobe’s documentation confirms that rule conditions and data elements can be used to control when tags fire.

Tealium iQ Approach

Use Load Rules to control where tags load. Define load rules that exclude PHI-related paths from marketing and analytics tags so they never load on those pages.

Across all three, the pattern is the same: designate PHI-risk pages, then use native conditions (URL matching, data elements, or load rules) to keep non-essential tags from running there.

Decision Framework

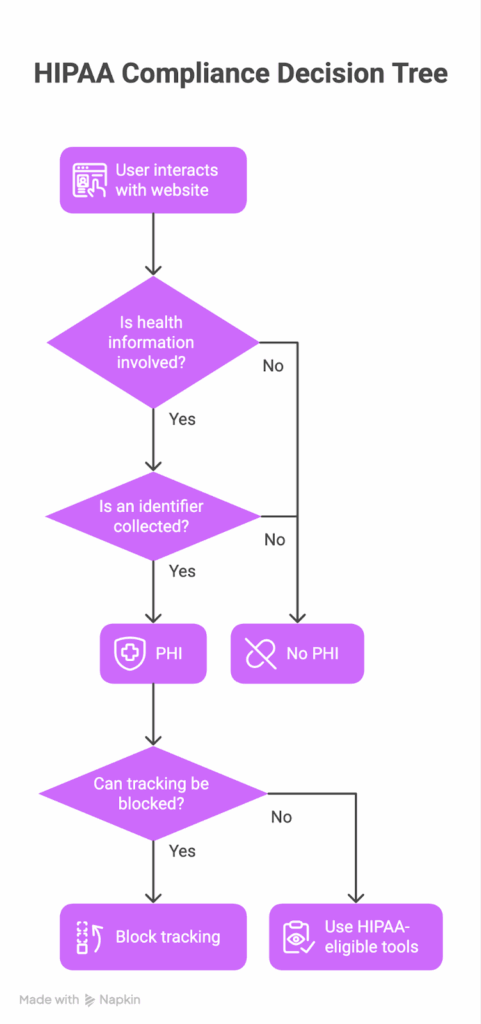

In our experience, teams move faster when classification is methodical and documented. Use this four-step screen and cite the same authorities OCR will.

1. Is health information present or implied?

HIPAA protects “individually identifiable health information” related to an individual’s health, care, or payment. If no health dimension is present, you’re in PII, not PHI.

2. Is there an identifier that could link data to a person?

Direct or indirect identifiers (e.g., names, email hashes coupled with other signals) are what convert health information into PHI under 45 CFR 160.103. If no identifiers are present, it’s not PHI.

3. Could the combination enable re-identification?

When multiple data points together can reasonably identify someone, treat the bundle as PHI. OCR’s tracking-technology bulletin underscores that transmitting identifiable health information to third-party tools can be an impermissible disclosure.

4. When uncertain, apply a conservative standard.

OCR has prioritized investigations into online tracking; ambiguous cases should be handled as PHI to avoid impermissible disclosures and breach obligations. Document the rationale in your risk analysis/assessment notes.

Record your determination (PHI/Not PHI/It depends) and controls in your risk analysis and ongoing evaluations. If a disclosure occurs, the Breach Notification Rule’s thresholds and timelines apply for incidents involving 500+ individuals.

Common Mistakes

Most HIPAA mistakes on websites start with comfortable assumptions. We see the same ones over and over again: teams equate “no name” with “no PHI,” and treat public pages as harmless. The Privacy Rule is broader and more contextual than that. Here are the patterns that create risk long before OCR or a plaintiff’s lawyer ever gets involved.

Mistake 1: “No patient name means it’s not PHI.”

HIPAA treats information as PHI when it relates to health and is individually identifiable. Identifiers aren’t limited to names; the Privacy Rule references direct and indirect identifiers. The key test is health information plus a link to an individual.

Mistake 2: “Public content is always safe.”

OCR’s tracking-technology bulletins explain that sharing identifiable health information with tracking vendors can bring it within HIPAA’s scope.

However, a June 20, 2024, federal ruling limited OCR’s stance as applied to IP addresses on unauthenticated public webpages; the court held OCR exceeded its authority on that narrow point. However, this ruling did not change expectations for pages or events that introduce health context or identifiers that link activity to an individual.

Mistake 3: “Redacting form fields is enough.”

Even if form inputs are masked, page context and events can still disclose health information tied to an individual.

OCR’s position is that disclosures of PHI to third parties for tracking require appropriate permission and, where vendors qualify as business associates, a BAA. The court decision above narrows one slice (IP on public pages) but does not negate broader obligations.

Mistake 4: “Marketing owns tags; HIPAA doesn’t apply.”

HIPAA obligations attach to covered entities and business associates regardless of which internal team deploys tags. Where tracking vendors create, receive, maintain, or transmit PHI on behalf of the entity, HIPAA business associate provisions may apply, bringing BAAs, safeguards, and the minimum necessary concept into scope.

Mistake 5: “We’ll wait for more OCR guidance before changing anything.”

OCR has already issued guidance on tracking technology (initially issued in 2022, updated June 26, 2024). Investigations and parallel legal actions have followed, and HHS did not appeal the June 2024 ruling that narrowed a portion of its bulletin, leaving the rest of its enforcement posture relevant.

Manual Approach vs. HealthData Shield AI

Most healthcare organizations start with manual processes to identify and limit PHI-related tracking. While this can work for small, static sites, it quickly becomes unsustainable as pages change, vendors update tags, and marketing teams deploy new tools.

Discovery and Classification

| Manual Approach | HealthData Shield AI |

| Developer manually inspects source code; must repeat for every page, subdomain, and flow | Automatically discovers all scripts, tags, and pixels across entire site in real time |

| Security team reviews each page to determine PHI status; edge cases require legal debate | AI analyzes page context and user flows to flag PHI risk consistently |

| Snapshot becomes outdated immediately; third-party updates often missed | Always current; tracks cascading script loads and dynamic changes |

| Time: Days to weeks per audit | Time: Minutes for complete visibility |

Configuration and Monitoring

| Manual Approach | HealthData Shield AI |

| Developer creates load rules and exceptions separately in each tag manager platform | Automatically generates blocking rules across GTM, Adobe, and Tealium |

| Quarterly or annual audits with no visibility between reviews | Continuous 24/7 monitoring with instant alerts for new tags on PHI pages |

| Marketing can accidentally deploy tags that fire on PHI pages | Blocks unauthorized tags automatically before PHI disclosure |

| Time: 1-2 hours per tag + ongoing risk exposure | Time: Automated with real-time protection |

Evidence and Compliance

| Manual Approach | HealthData Shield AI |

| Screenshots and spreadsheets manually compiled when OCR inquires | Structured evidence exports with timestamps available on demand |

| Evidence becomes stale quickly; difficult to prove continuous compliance | Audit trail shows ongoing monitoring and enforcement |

| Time: Days to assemble for investigation | Time: Minutes to export reports |

The Bottom Line

For a mid-sized healthcare organization with 200+ website pages, manual compliance typically requires 80 to 155 hours for initial setup and more than 100 hours per year for ongoing maintenance. HealthData Shield AI reduces this to 2 to 4 hours for initial integration and automated ongoing maintenance, a roughly 90% reduction in compliance effort.

How HealthData Shield AI Closes the PHI Gap

HealthData Shield AI operationalizes HIPAA compliance by continuously scanning all pages to identify scripts and tags, analyzing content and user flows to flag PHI risk. It then automatically blocks marketing tags on PHI-designated pages across GTM, Adobe, and Tealium.

Real-time alerts surface changes early and allow teams to address them before they escalate, while comprehensive logs provide audit-ready evidence for OCR inquiries with one-click export.

See how your own pages map out in real time with HealthData Shield.

Next Steps

This Week

Audit PHI-sensitive pages (portals, telehealth, condition pages, forms) and verify which tags and pixels fire where. Note your own edge cases (for example, condition pages plus identifiers) and, when in doubt, treat the data as PHI. If you discover that PHI has been disclosed to third parties, HIPAA Breach Notification timelines may apply.

This Month

Implement tag manager blocks on PHI-designated routes so marketing, retargeting, and session replay cannot run on them. Document your PHI determinations and controls in a risk or privacy impact analysis, and update public disclosures if tracking practices change.

This Quarter

Complete a privacy impact assessment covering edge cases and tracking technologies, keep evidence for audits or OCR inquiries, and train marketing, web, and product teams on PHI boundaries. Ensure you have runtime visibility in the browser so you can detect and block PHI disclosures early, rather than hearing about them through complaints or regulators.

How Feroot Closes the PHI Gap on Your Website

If your teams are already wrestling with HIPAA tracking pixels, tags, and “is this PHI or not?”, HealthData Shield AI simply takes the guesswork out of it.

It continuously flags where tracking technologies intersect with PHI context, blocks what shouldn’t run, and leaves a clean trail of evidence you can hand to auditors or privacy counsel.

If you want hands-on help, request a demo and see your own pages mapped in real time. If you’re still scoping the problem, start by downloading the HIPAA pixel compliance checklist and use it to pressure-test your current setup.